How the Mind Traces the Dead:

And Has to Learn it Like Rachmaninoff

’Tis a fearful thing

to love

what death can touch.¹

You know how, when you were just a wee thing, you’d return to school in January with rosy cheeks and chapped lips—but instead of a warm, smiley welcome, your formerly cheerful fifth-grade teacher would return to class all amped up like a cheap appliance?

The change had a single source --- formidable urgency she had about her curriculum which she had every intention of putting on a luge and speeding straight at all of us eleven-year-olds at two hundred miles per hour between January 3rd and March 31st. She knew what we knew: come April, we’d all stop caring simultaneously. On mission was Miss Barsom. And so are we.

Here at Coming to the Nuisance, they’ll be no more fun and games. No more hiking, hunting or otherwise dawdling or delaying. I’m at the starting ramp and we’re about to go hard at some of the more difficult things in my file.

You see, over the holidays, I had a simple revelation about these materials. I realized they all fell into two main categories: good news and bad news. And somehow a logjam broke. These letters are almost assembling themselves!

Now, since I’m of Irish descent, I thought I would go with the bad news first. We tend to circle around it like moth to flame. So, today I want to share one of the most troubling pieces of bad news: in acute grief, there’s an excruciating aspect that, in a technical, practical sense…

there’s actually nothing for it.

These words were hard to write. They’re even harder to say. But I mean them as comfort, not provocation. Because there’s a way in which this is true. You’ll see. And my hope would be that it dignifies how disorienting the beginning is.

Let me illustrate what I mean. Stories here are better than statements.

I recently heard one of the most popular grief gurus in the country on a podcast. His name is David Kessler and he’s written several bestselling books on the subject. Not someone I’d heard of or follow; he’s a secular guy I took it, but a deep kind of thinker.

He’d had some profound losses in his life; in particular, I think he lost his mom when he was a teenager or young adult, and that was what drew him into the work to begin with. But the interviewer asked him about a more recent loss: his son.

He said that after his son’s death, when he finally dragged himself months later to a grief group, he sat there totally mute, unable to open his mouth or even look up from the floor at the other grievers. No one at the group knew who he was, a well-known grief writer.

And he described how he sat there, five feet from a table piled high with books he’d written. And he said the only cogent thought that came to him then was this desire suddenly to call all the people he’d counseled over the many years, the hundreds, who’d lost children, and say to them: I am so sorry. I had no idea.

And I guess this is what I believe about vertiginous, terrifying loss. I think that in that first season, we just have no idea. Words won’t reach it --- even they know to run off across the grass toward the woodline.

There will be lots of caveats as we traverse this grief territory, and here comes numero uno: you might be tempted to remind me that yes—this entire Substack is, in some way, dedicated to what might be for it. Some of what might help in grief. That art and stories can be a call and response with grief. And isn’t God with us in grief? How can it be that there’s nothing for it or we have no idea when this whole project is partly my tiny contribution to exactly that?

Just trust me, friends—both can be true and are true in some sense. There’s so much tension and contradiction in grief; we’ll see our fair share in just this letter. And we’ll have to hold opposed ideas in our minds at the same time. Grief will ask this of us over and over.

Here’s another truth-with-tension that helps launch us deeper into the file:

Do you remember last July when I pulled Nicholas Wolterstorff’s Lament for a Son off the shelf in the aftermath of the Texas floods? As I was writing that piece, sans birds, I came across an interview in which Wolterstorff blithely offered one of the most stunning insights about acute grief I’ve ever seen.

He said:

My problem was not Grief with a capital “G”; my problem was that Eric was dead.

That’s it. Right there. It’s totally tautological. The problem with death is, um, death. Not some abstract therapeutic pedagogy you’re supposed to dutifully check through as the assigned griever.

I remember so actively, passionately trying to accomplish this grief thing after my mom and sister died: Someone! Please! Tell me! Give me the list! Let me start checking it off! So I can get from where I am to literally anywhere else!

But it turns out the only real solution to the problem of death would be a full-blown Lazarus redux, like resurrection. Not grief. Not birds.

It just so happens the human brain does not like this puzzle one bit either. That’s essentially how the brain sees death: a problem it cannot seem to solve.

Thankfully, scientists and researchers have been quietly studying the brain’s response to grief for the past few decades. From the file this month comes a book recently published called The Grieving Brain by one of those researchers, Mary-Frances O’Connor (told ya, Irish), founder of the Grief, Loss & Social Stress Lab (GLASS) at the University of Arizona.

Her research offers insight into the monumental struggle the brain has in comprehending this sudden absence—even in those whose loved ones had lengthy illnesses.

O’Connor explains:

The idea that a person is simply no longer in this dimensional world is not a logical answer to their absence, as far as the brain is concerned.

You see, there’s a part of our brains that’s almost frighteningly neutral. Not the meaning-making parts, they’re more nuanced -- - what we might call our hearts and souls and minds. But there’s also a no-nonsense functionary in there: a problem-solving machine trying to make sure you get what it believes you need, ASAP. (Put a pin in that for when we get to substance use—the operative and hair-raising phrase being: what it believes you need.)

We can understand the brain’s confusion better when O’Connor lays out how it sees our worlds and organizes them to achieve survival.

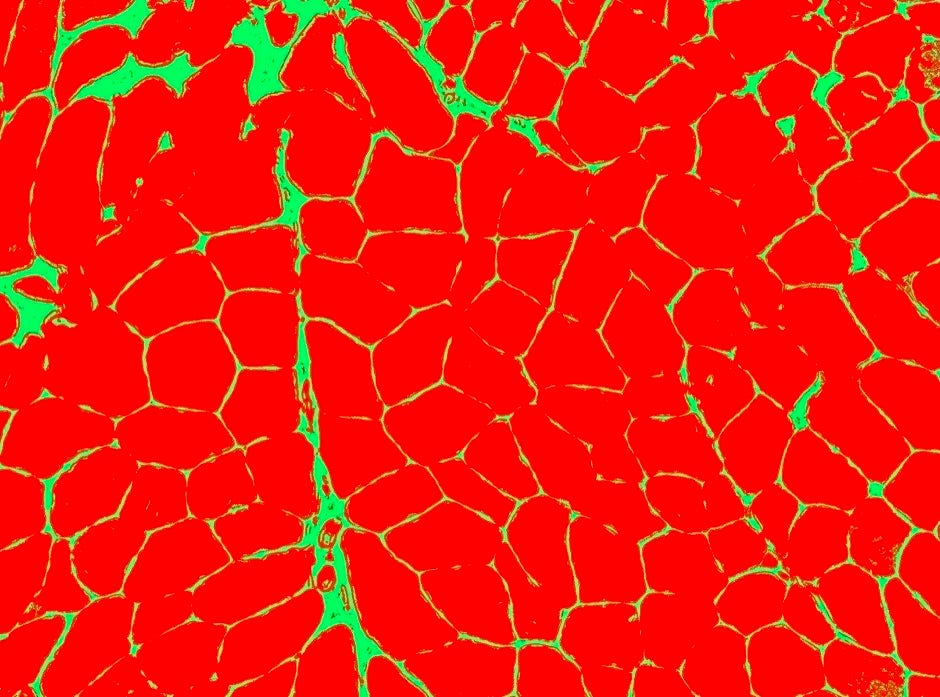

O’Connor says the brain uses “maps” of our worlds, like Google Maps in our heads, to navigate the pathways to resources—food, water, shelter—and, as mammals evolved, those resources expanded to include protection, caregiving, and love.

Once the map is built, the brain can then return to what it’s really good at: patterns, predictions, and habits. In short, it can stop thinking so much. Which is perfect because this part of the brain doesn’t actually fancy thinking. It’s always on a pretty ruthless “econ” setting.

Because the brain excels at prediction, it often just fills in information that isn’t actually there. It completes the picture it expects to see. Which means it just keeps placing the missing person into the map, because their absence reads like a violation.

When the brain is forced, finally, to face the missing piece, researchers can see a measurable signature of that mismatch in brain activity. Like a zap that reads on an EEG.

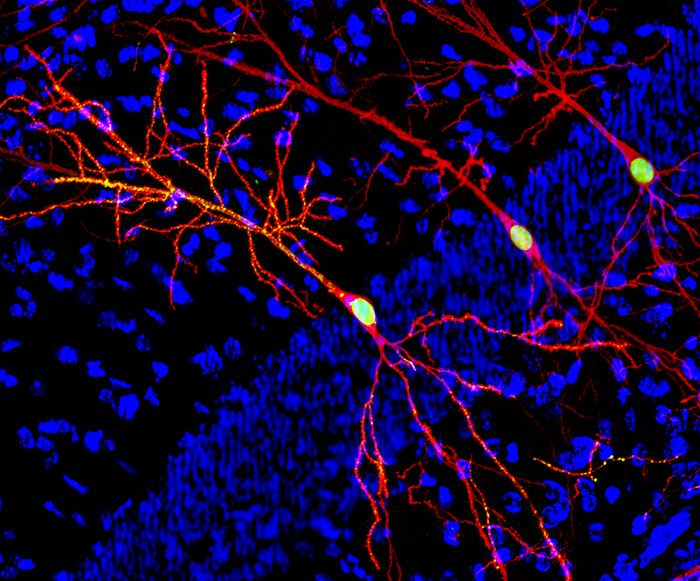

Low and behold, other mammals also use these virtual maps, so researchers have been able to conduct animals studies where they’ve identified the set of neurons that fire when the critters arrive at one of their resources. They called them ‘object cells’.

To their amazement, they found a separate set of neurons that fire when the animal approaches a place along their route where a resource used to be. They called these “object trace cells”. I cried when I read that. I think a few years of my life could be explained by that one word: trace.

O’Connor summarizes:

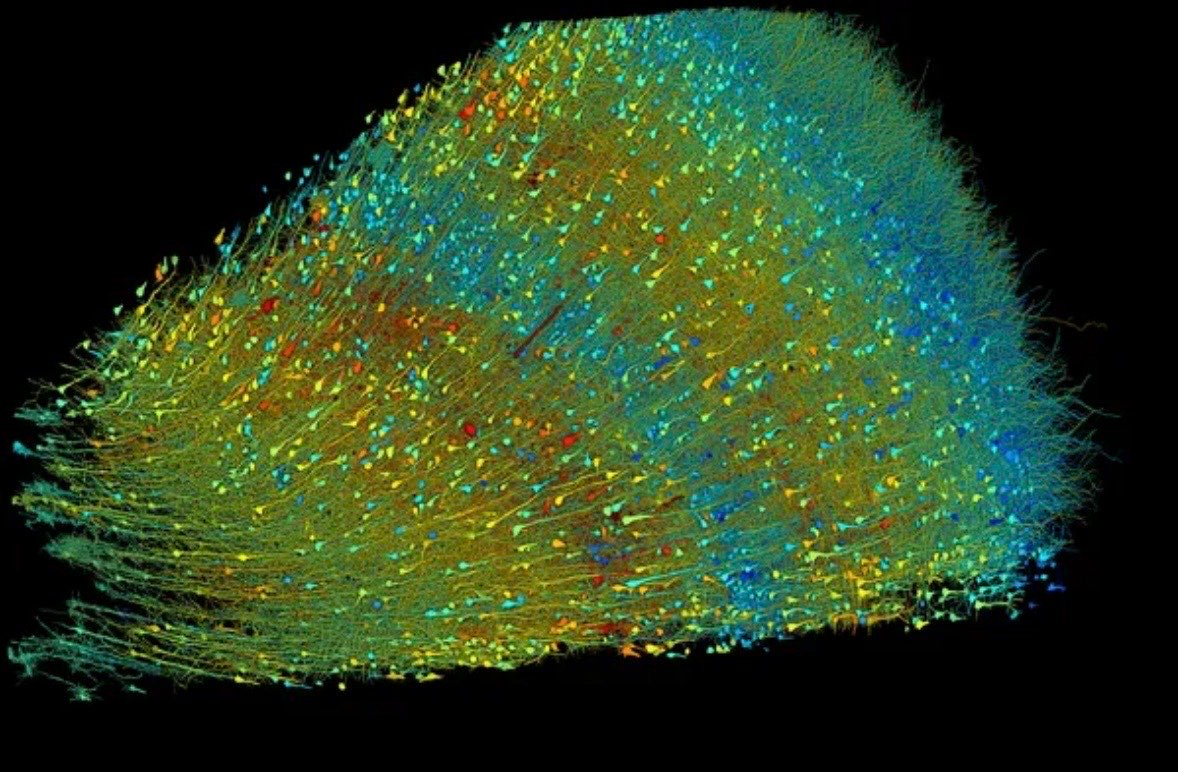

Grieving requires the difficult task of throwing out the map we have used to navigate our lives and making a new, revised cartography.

The reason she says she wrote the book at all was to get one simple idea out to the public:

…the process of grieving in the end is a form of learning.

The brain must practice and learn death. So time does, in fact, heal. But it’s not the time that’s helping, exactly. It’s the practice. For the brain, death is an acquired skill—like serving an ace in tennis, or playing a Rachmaninoff concerto, or kicking a 65-foot-long field goal.

Let’s close with one more thing from the file. It’s a tough passage from a grief memoir called Humanity Is Trying by Jason Gots, who lost his sister in mid-life. It haunted me when I first read it, but I so appreciated that he was brave enough not to tie things up at the end. I could picture the publisher bristling.

It was years ago when I threw this in, and at the time I connected with it. I don’t resonate with it as much now. Thank God. But for a couple years, I’d say it captured something of my experience.

He writes:

I don’t know what closure is. Or mourning, either, to be honest. Here I am, years later, still looking for—something. It’s like wandering around a vast and vaguely familiar mansion in a dream, rattling every doorknob on some urgent but undefined mission…

For a long time, I consoled myself with the thought that I had learned something important from her death—something about the preciousness of life… But people don’t die for the benefit of our personal growth. There’s no lesson here. No neat binding into which the story will fit. No way, finally, to bring her back to life or to let her go, either.

Jason Gots, Humanity Is Trying: Experiments in Living with Grief, Finding Connection and Resisting Easy Answers

I’ll close with this today because it seems to me such a real place—and pure sans birds—and it feels right to honor it as we begin in earnest this journey to the heart of the file. I promised hard today, and this is hard.

I’m grateful to report I didn’t get stuck in the place he describes although I recognize it. I moved on and so did my file. So take from this whatever might be helpful and toss the rest off your snowmobile.

I’ll see you guys next month and play some MC Hammer and dance around your kitchen to shake it off.

Truth: Where can I flee from your presence? If I go up to the heavens, you are there; if I make my bed in the depths, you are there. —Psalm 139:8

Tip: MC Hammer Can’t Touch This, lyrics, from my new playlist, Funk You.

Tote: Obsessed with Chai this winter. My fave tea place: Jenway.

I’m always so grateful to hear from my readers! Please feel warmly invited to leave a comment for me on Substack. xok

¹ Epigraph: Chaim Stern, “’Tis a Fearful Thing.”

Leora!! Oh my Lord! I seriously cannot imagine a reader I would rather touch than YOU!! I’m so grateful you would take the time. My file in so many ways started with you and Lis in your Needham office. Sending So Much Love Your Way!!

Beautiful mom!